Sound engineers and production staff often confuse sound system tuning and sound system toning. Tuning a sound system involves objective goals and measurements. Toning a sound system is a subjective, artistic endeavour.

Audio can be scary because it’s invisible. Therefore, many people believe all audio engineers have identical wizard-like abilities: they are expected to walk into any room, anywhere, and create magic sound with their golden ears.

In reality, system technician and mix engineer are separate jobs. Although both use their ears and are often performed by the same person, they require different skills and goals. Let’s stop trying to combine the two jobs into one and get to work. In this post I would like to share some of the information from Bob McCarthy’s original article, Toning Your Sound System.

Sound System Tuning

“Tuning a sound system: Adjust for uniform response over the listening area, with minimal distortion, maximum intelligibility and best available sonic imaging.”

The goal of tuning a system? To have the same sound everywhere. That means having the same level, same frequency response, and same intelligibility in every single seat.

Is that attainable? No. Our atmosphere is a harsh place for sound waves. But do we strive for faithful delivery to all ears? Absolutely. We know our children will never be perfect, but we love them anyway.

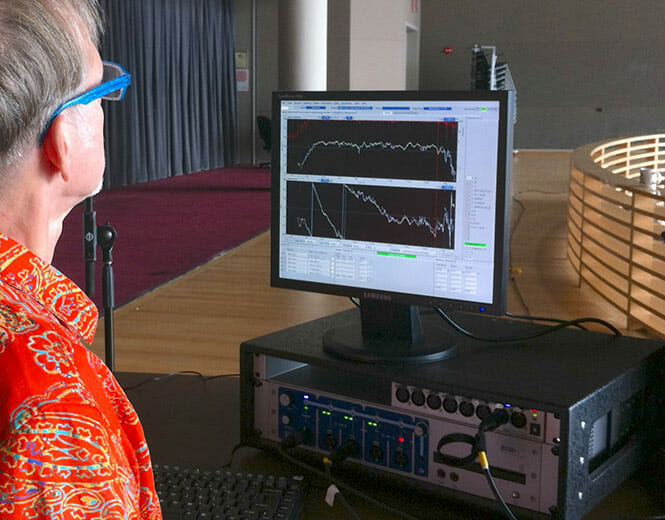

Tuning can be objectively measured. We have tools that we can use to measure exactly how close we are to achieving our goal, and therefore declare success. With software and hardware such as SIM, SMAART, Easera, and SATLive, we can perform a transfer function to measure relative level, delay/phase, and frequency response. Toning, in contrast, is a subjective process.

Sound System Toning

“Toning a system is the setting of a bank of global equalisation filters at the output of the mix console that drives the sound system. If you want to set it by ear fine. If you want to set it by 10,000 hours of acoustical analysis containing mean/spline/root squared/Boolean averaging then go for it. There is nothing at stake here. Nothing to argue about. The global equaliser is just an extension of the mix console EQ.” – Bob McCarthy

Sound engineers just love to argue on forums and in trade magazines about exactly how to do this. The classic advice is to yell “Check!” into a microphone over and over while moving filters on a graphic EQ until everyone’s ears bleed, and call that success. Other engineers choose to play songs that they know well. I like pink noise because it’s fast, you can play it quietly, and has no emotional connection.

The truth is, it doesn’t matter. It’s not a science and we don’t need to make it one.

“Good toning enhances the musical quality, or natural quality of transmitted sound. Good tuning ensures that the good (or bad) toning makes it beyond the mix position” – Bob McCarthy

It is important to keep these concepts in perspective because audio is primarily a subjective and emotional business. We can’t see it, so even those of us who work in the field feel very strongly about what happens in this invisible space. My guess is that you’ve seen an article or two about the advantages or disadvantages of a “flat sound system.” That argument is pointless, because you can’t dance to white noise. Music is all about dynamics, not equal power per frequency band.

I have to admit that initially there is a temptation to draw straight lines on the analyser screen, but it will drive you insane. Besides, so many other tasks come first in tuning a sound system: checking driver functionality and polarity, aiming the speakers, adjusting splay angles and relative level between speakers, setting crossovers, phase alignment, intelligibility analysis, and treating reflections. Equalisation is the final step in the process.

I once worked with a sound engineer who often repeated a story of a Meyer Sound technician coming in and “SIMing the sound system,” only to leave it sounding terrible. I’m sure he’s right; to him it sounded terrible. But it probably also sounded terrible at every seat, because it was properly tuned. His frustration comes from this breakdown in communication about where system optimisation ends and artistic expression begins. As Bob McCarthy says in our interview, “Draw me a picture of how you want it to sound and I’ll paint that in every seat. But you can’t paint on a canvas with a giant rip in it. That’s no fun.”

Here’s a common error: Measure at 15 different places around the room. Average them together. Apply the reverse settings to your EQ.

How do I know?

Cause I used to do that shit all the time!! I had a hand-held RTA (real time analyser) that would allow you to put measurements into memory, average them, then flip them to make settings to a 31-band graphic EQ. First of all, an RTA and graphic EQ are never appropriate for system tuning. (See my discussion with McCarthy below at 24m22s.) Second, it’s really important to know what is happening with your audio in different parts of the room, so averaging different areas together is misleading. As McCarthy says, “Why bother to take samples all around the room if you’re not going to do anything about the differences around the room? It’s just a waste of time.” Also, the math doesn’t work out because measurements of destructive summation (cuts) are often narrow and deep while measurements of constructive summation (boosts) are often wide and short.

Take away message: You don’t use an audio analyser to make something sound good; you use it to make it sound the same everywhere.

Have you experienced this communication breakdown? Comment below.